Clik here to view.

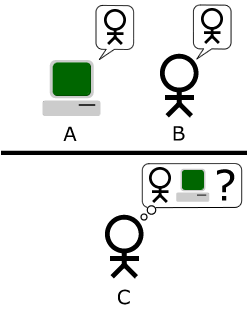

The “standard interpretation” of the Turing Test, in which player C, the interrogator, is tasked with trying to determine which player – A or B – is a computer and which is a human. The interrogator is limited to only using the responses to written questions in order to make the determination. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Turing Test is in the news this week, first with a wave of hype about a historical accomplishment, then with a secondary wave of skeptical scrutiny.

The Turing Test was originally contemplated by Alan Turing in a 1950 paper. Turing envisaged it as an alternative to trying to determine if a machine could think.

I propose to consider the question, “Can machines think?” This should begin with definitions of the meaning of the terms “machine” and “think.” The definitions might be framed so as to reflect so far as possible the normal use of the words, but this attitude is dangerous, If the meaning of the words “machine” and “think” are to be found by examining how they are commonly used it is difficult to escape the conclusion that the meaning and the answer to the question, “Can machines think?” is to be sought in a statistical survey such as a Gallup poll. But this is absurd. Instead of attempting such a definition I shall replace the question by another, which is closely related to it and is expressed in relatively unambiguous words.

His replacement question was whether a machine could pass the test that now bears his name. In the test, a human interrogator is in a separate room from another human and a computer. The interrogator can communicate with the other human and computer only via teletype (or via texting or online chat in a modern version). If the interrogator cannot distinguish which respondent is the human and which is the computer, then the computer passes the test.

So, what happened in the recent event that the news stories are discussing? In summary, a computer program pretended to be a 13 year old boy with only a limited understanding of English. With a conversation limited to five minutes, the system managed to fool 33% of the human interrogators. Fooling 30% or more of the interrogators is considered to be passing the test.

Now, the five minute conversation and 30% threshold does go back to something of an offhand remark in Turing’s original paper.

I believe that in about fifty years’ time it will be possible, to programme computers, with a storage capacity of about 109, to make them play the imitation game so well that an average interrogator will not have more than 70 per cent chance of making the right identification after five minutes of questioning.

But the imitated human only being 13 years old, and a foreigner with English as a second language, stacks the test in a way that I’m pretty sure Turing would not have considered valid. How many of them would have been fooled if the interrogators had been expecting an adult who was fully conversant in English? Consider what kind of conversation you might expect from a typical uncooperative 13 year old in broken English, versus from an articulate adult. The lower maturity level and language barrier enabled the program to mask a huge gap in technical capability.

That’s not to say that this isn’t an accomplishment, but we’re not to the stage yet where most of us will be tempted to think a program who fooled these interrogators, in the limited fashion described, is a “thinking machine.” But it is getting close enough for us to ask the question, does this mean the test that Turing originally proposed is flawed? If we say yes, are we merely moving the goal post back when it comes to regarding a machine as thinking?

Turing might have been a bit naive to consider a 30% success rate (from the point of the computer) after a five minute conversation, as a meaningful threshold. He also predicted that a machine with only 125 megabytes of memory would be able to do the job, which isn’t true, and he predicted that by the time we had achieved this success rate with the test, that we’d already be commonly considering computers as thinking entities, which hasn’t come to pass.

In his defense, these predictions were all made in 1950. The central thesis of the Turing Test is that it is meaningless, scientifically, to ask if a machine can think, only to see if it can convince us it can think. In 1950, it was probably reasonable to assume five minutes and 30% was a meaningful threshold for this. We have to consider how people in 1950, unfamiliar with the last 64 years of computer technology, would have reacted to the best of the modern chatbots.

Ok, but then the question is, what would be a meaningful threshold by today’s standards? Personally, I wouldn’t consider the test to be meaningful if a machine wouldn’t be required to converse with a human for as long as the human needed to take to make a confident decision. And the test would need to resemble Turing’s original configuration involving choosing between a human and a machine, or the machine would have to pass at the same rate as an actual human being. Granted, this is a tough standard, but it’s hard for me to see people being tempted to conclude there’s another mind there without something like it being met.

And, of course, we still have the old objection that the Turing Test is really measuring for humanity rather than intelligence. But I think asking humans to regard a machine as a thinking entity is asking them, to some degree, to anthropomorphize it. We already have a built in tendency to do that (think how many people do it with their pets, their cars, etc), so the threshold isn’t as insurmountable as it might look.

One thing Turing did say in his paper that is still critical to understand: the hardware is important, but the magic sauce of this will be in the programming. And that’s still perhaps the hardest barrier to be surmounted, although with ongoing progress in neuroscience and AI research, I personally think we’re going to get there.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. But the philosophical question remains. Does a computer passing the Turing Test, at any level of difficulty, really tell us anything about its internal state, whether it can actually think, whether it is conscious, whether it has an internal experience? The question is, can it successfully emulate that experience to us and yet not have it at some functional level?

But the philosophical question remains. Does a computer passing the Turing Test, at any level of difficulty, really tell us anything about its internal state, whether it can actually think, whether it is conscious, whether it has an internal experience? The question is, can it successfully emulate that experience to us and yet not have it at some functional level?

Your answer to that question probably depends on your attitude toward philosophical zombies, whether you believe it is possible for a being to exist, to behave and function as though they are conscious, to the extent that everyone around them believes they are conscious, but not actually be conscious? If yes, then you’ll probably be slow to accept a program, computer, AI, or machine as a fellow being.

Of course, it’s all very well to talk about this in an abstract philosophical fashion. Many of us, whatever our position, may think differently after we actually have a conversation with such an entity.

Related articles

- That Computer Actually Got an F on the Turing Test (wired.com)

- Chatbot probably did not pass the Turing Test in Artificial Intelligence (robohub.org)

- Re: Turing test (io9.com)

Clik here to view.

Tagged: AI, Alan Turing, Artificial intelligence, computer consciousness, Consciousness, Eugene Goostman, Intelligence, Mind, Philosophical zombie, Philosophy, Science, Turing, Turing test Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.